His name floated through my childhood. I can recall hearing it uttered, but not anything specific that was said about him. Certain grown-ups uttered it, that is. Not my father. Not my maternal grandparents and aunt, who lived across the street from us. Not my other maternal aunt, who lived on Long Island, and whom we saw often. Perhaps not even my mother, though I don’t see why I don’t remember her saying “Armando” when the grown-ups who did say it were her New York City friends: my Venezuelan godmother, Josephine Arcilagos, and George Anderson, with whom my parents had lived in Greenwich Village after World War II, when I was a baby. My mother had worked with Jo at NBC during the war, while my father was overseas in north Africa and Italy with the Army Air Force. Armando had worked at NBC, too.

His name floated through my childhood. I can recall hearing it uttered, but not anything specific that was said about him. Certain grown-ups uttered it, that is. Not my father. Not my maternal grandparents and aunt, who lived across the street from us. Not my other maternal aunt, who lived on Long Island, and whom we saw often. Perhaps not even my mother, though I don’t see why I don’t remember her saying “Armando” when the grown-ups who did say it were her New York City friends: my Venezuelan godmother, Josephine Arcilagos, and George Anderson, with whom my parents had lived in Greenwich Village after World War II, when I was a baby. My mother had worked with Jo at NBC during the war, while my father was overseas in north Africa and Italy with the Army Air Force. Armando had worked at NBC, too.

For years, Jo and George visited us in our suburban home in Teaneck, New Jersey. Sometimes, George brought his lover, Ed. Jo visited the most often. We children would wait to spy her on the horizon of our long street, would watch her figure grow gradually larger until, confident at last that it was Jo, we’d burst towards her on roller skates and bikes, circling her stately approach down the final blocks like noisy gulls around a docking ship.

Armando never came. My mother had another New York friend, Aurora, who was also mentioned often, and she never came either, so I didn’t really think much about Armando’s absence. The gift-laden New Yorkers who did come were entertaining enough, exotic birds amid the robins and wrens and cardinals of our otherwise ordinary neighborhood of tumbling children and aproned housewives and men who were gone before we got up in the morning and who came back just in time for dinner.

At some point, Armando stopped being spoken of. I don’t recall hearing him mentioned at all during my teen years. The next time the name surfaced was in 1971. I was 26, married, and living in the tiny rural town of Hickman, Maryland. My husband, Leo, was a junk sculptor. He eventually was able to make a good living from his art, but at that time he was just starting out. He’d sold one piece, to a friend. I was a part-time teacher in the local high school, stumbling through teaching Home Ec, in which I was neither qualified nor interested.

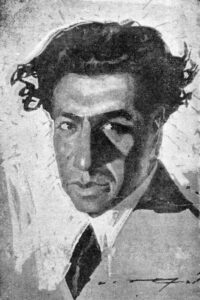

During one of our weekly phone conversations, my mother told me that an old friend of hers, Armando Zegrí, used to have a gallery in New York that specialized in South American artists, and that he might be willing to look at Leo’s work. She didn’t know the address or even if it was still in operation, but she could find out. I told her no thanks because Leo’s art wouldn’t fit. She didn’t press it. She had made the offer very casually, and I had as casually turned it down.

By the summer of 1976, my marriage was faltering, and I was contemplating a trial separation. I couldn’t think beyond that, even though I had a beguiling lover, Victor, who wished I would, and even though Leo had warned me that if I left, even temporarily, he’d move for immediate divorce. I craved some time and space alone, but I was frozen by indecision and wildly conflicting desires, and by the sense of an enormous finality hovering over me. I sent my parents a long, emotional letter in which I berated myself for my warring emotions. I felt selfish and wrong. I was hurting two men I cared about, and getting all of us exactly nowhere.

My mother replied with an equally long and emotional letter. First, she sympathized with me and encouraged me. Then she made a dramatic confession: she had lived through a similar dilemma with my father and a man she met while my father was away at war. As I read her description of the affair, a sudden certainty struck me that this old lover must be the phantom Armando, and that he was my biological father.

I had always felt “different” from my siblings. I had different interests and different kinds of friendships. I also looked different from my three sisters and one brother, who were all blondes. I didn’t think too much about that, however, as my other brother, Brent, was dark like me. I was always being asked my nationality and disbelieved when I answered German and English. To silence the doubters, I devised a theory that Brent and I possessed throwback genes to Australian aborigines. A great-aunt claimed that someone in the Sickels family had lived in Australia long ago. (It turned out that Brent had gotten his darkness the same way I had, from Armando.)

At the close of her letter, my mother worried that I would think less of her because of her revelation. I wrote back immediately to reassure her. But I didn’t ask about my paternity. I feared upsetting the handsome, gentle man whom I had always considered my father, Ralph Sickels. I feared resurrecting old troubles and hurt between my parents. I feared that if I were mistaken, my question would be some kind of insult.

Almost as soon as I put the letter back into its envelope, I began to consider that I could be mistaken. My mother hadn’t told me her lover’s name. She’d written that the whole drama had played out before any of we children were born. I had to believe her. Not to believe her meant I’d have to challenge her, and by that challenge, risk changing forever, perhaps for ill, our relationship and perhaps, also, my parents’ marital relationship. I thought that if it were true that my father was not my father, she would have said so. It was only one step more for her to take.

I dredged up for myself, as I had so often for suspicious others, the improbability of a close-knit family with two illegitimate children, spaced years apart, whose status no one acknowledged in any way, either overtly or by subtle, discriminatory behavior. It would have been a situation known to all my grandparents and aunts, to my godmother and any number of my parents’ friends, yet no one had ever let one hint escape. Was such colossal conspiracy possible? Reason and caution insisted I could well be wrong. Reason and caution — and fear — kept me quiet. Deep down, I knew I was right about Armando, but I pushed the idea deeper still. I told no one about the letter. The topic of Armando never arose between my mother and me again.

SEARCHING FOR ARMANDO is available as an e-book through Amazon (for Kindle), Barnes & Noble (for Nook), and iBooks. The limited edition print book is only available directly from me at $25, including shipping. E-mail me at lasirenapress@gmail.com to order a copy.

Permalink

Reading this excerpt from your book SEARCHING FOR ARMANDO brought back the heavy burdens and thrills of discovery I experienced when I first read the book. I feel I need to re-read it as I have been doing with Bradbury and some other favorites.